SecuringAV: The Remote Desktop Attack on a Florida Water Treatment Plant

For each column in this series, rAVe writer Paul Konikowski takes a deeper dive into a recent security event or data breach, shedding light on supply chain vulnerabilities, infrastructure and cyber-physical security.

For each column in this series, rAVe writer Paul Konikowski takes a deeper dive into a recent security event or data breach, shedding light on supply chain vulnerabilities, infrastructure and cyber-physical security.

In my last “SecuringAV” column about the Nashville Christmas morning bombing, I did my best to define what “infrastructure project” meant using the definition from Executive Order 13858*. It states, “‘Infrastructure Project’ is a project to develop public or private physical assets that are designed to provide or support services to the general public in the following sectors…Broadband internet; pipelines; stormwater and sewer infrastructure; drinking water infrastructure; cybersecurity; and any other sector designated through a notice published in the Federal Register by the Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council.”

*Note this E.O. 13858 was recently revoked by Executive Order 14005, but the new Executive Order 14005 did not define infrastructure.

Even if we cannot all agree on what “infrastructure” is or isn’t, I hope we can agree that some major infrastructure is being attacked, whether it be a gas pipeline or a water treatment plant in Florida …

On Feb. 5, 2021, a water treatment plant operator in Oldsmar Beach, Florida, noticed his mouse cursor was moving around his computer screen, seemingly on its own. The rogue mouse opened software and boosted the level of sodium hydroxide (aka lye) in the water to be over 100 times the normal level. The only way this was detected was because the operator saw the mouse moving and quickly reset the system to the right level.

Authorities in the area did their best to reassure the public that the sensors would have stopped water flow long before it was released as part of an emergency management system. But what if the sensors were also hacked?

In the Stuxnet attack, the system interface panels were also hacked into displaying incorrect system data. So how can we trust the sensors and the screens displaying the current system status are accurate? Thus, we have a few lessons to learn from water treatment attacks, and how they might apply to AV systems:

First, we have to address the power and responsibility of the human who noticed the mouse was moving. While it is scary to think our water safety comes down to someone noticing a mouse cursor moving, this person did their job. Most importantly, they alerted local, national and global leaders to the problem. Had this operator not said anything, it may have been swept under the rug. That employee deserves an immediate raise.

Second, we can’t purely rely on humans to notice cursors moving to protect our infrastructure. Imagine if other detection systems worked like this; if physical security was purely based on seeing the bad actors on camera, or if theft was only based on seeing the person stealing something. The best security systems are a combination of technology and video monitoring.

Last, it’s critical to realize how vulnerable our AV devices are to the same “mystery mouse” attacks. Following the steps laid out by Anthony Tippy in his blog post, one can easily fire up Shodan.io and find some AV devices that use default passwords or no passwords at all — anyone can access them.

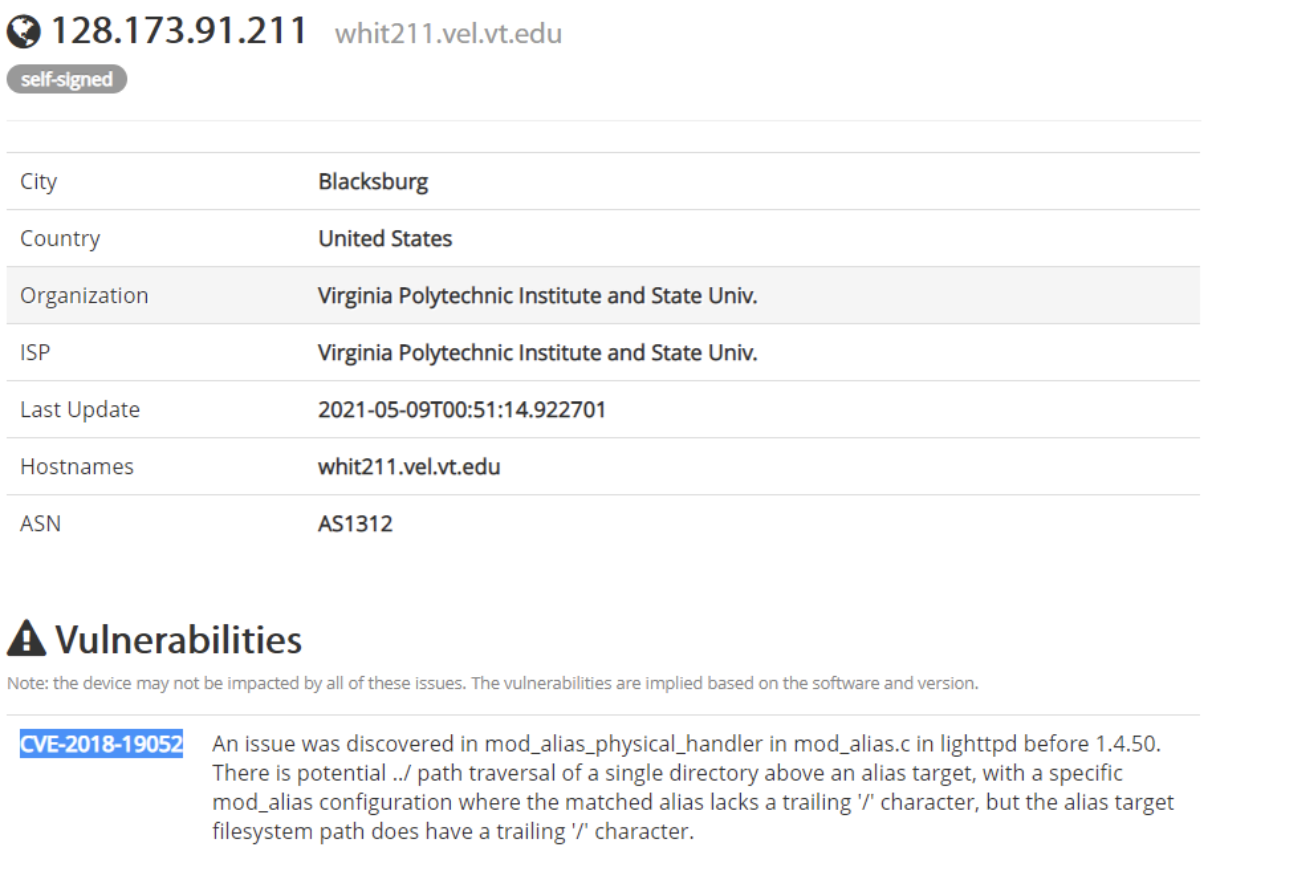

For example, a quick search for AirMedia reveals a device at Virginia Tech and a known vulnerability:

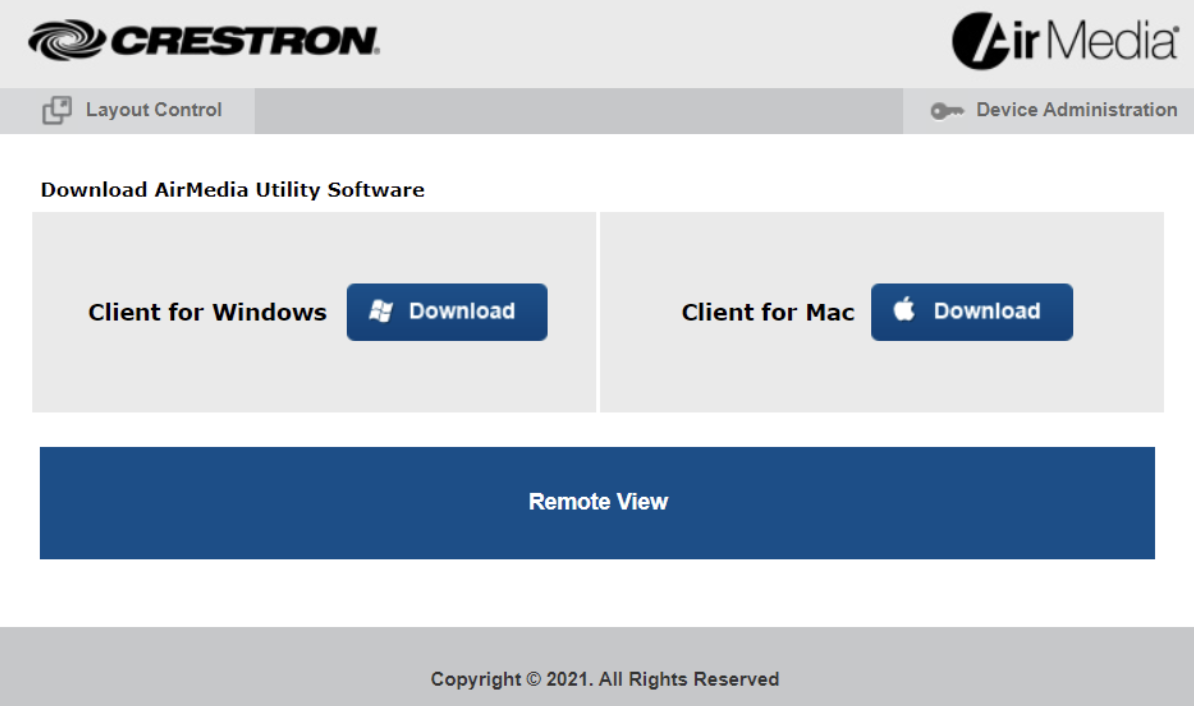

Clicking a link on the page brings me to the webpage that is served up by the AirMedia Device:

Clicking a link on the page brings me to the webpage that is served up by the AirMedia Device:

Just like the water treatment attacker, I can remotely click the mouse on these buttons. Luckily, the school changed the Device Administration password, but I can still get a live view of the presentations.

Just like the water treatment attacker, I can remotely click the mouse on these buttons. Luckily, the school changed the Device Administration password, but I can still get a live view of the presentations.

In this case, I have not done any real harm, but it’s not difficult for someone to get access to AV systems. This is why it is so important to segment your networks and apply least privilege rules and role-based access control to limit who can access different administration functions or presentations over the internet.